Training and Preparedness Are the Pillars of Maritime Safety with Lessons Learned from Regulations and Historic Accidents

Disasters like the Herald of Free Enterprise, Estonia, and Costa Concordia revealed how the lack of proper training, leadership, and coordination can turn emergencies into tragedies. These incidents led to key reforms, including the ISM Code, improvements to SOLAS, and updates to the STCW Convention. This article explores how continuous training, realistic drills, and human factor management are essential to prevent emergencies and respond effectively. It serves as a practical guide for captains, officers, and safety managers committed to building a strong safety culture on board.

Robert Garabán Garcías

9/2/20258 min read

Crew training and preparedness are at the core of maritime safety. Throughout history, the merchant marine has learned—often through painful experiences—that the difference between a successful evacuation and a chaotic tragedy lies in the human response during an emergency.

Incidents like the Herald of Free Enterprise (1987), the Estonia (1994), and the Costa Concordia (2012) clearly demonstrate this. In each case, a lack of adequate preparation, poor emergency procedures, and crew coordination failures had catastrophic consequences. These tragedies not only marked turning points in maritime history, but also triggered essential regulatory reforms:

The ISM Code (International Safety Management) was introduced after the Herald of Free Enterprise to require formal safety management systems for shipping companies.

The Estonia disaster led to stronger SOLAS regulations, particularly for ro-ro vessels and passenger evacuation procedures.

The Costa Concordia tragedy renewed the focus on leadership, crowd management, and mass evacuation training within the framework of the amended STCW Convention (1978).

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has since established clear standards. Every seafarer must be certified under STCW, participate in regular drills, train in firefighting, sea survival, first aid, and—most importantly—commit to continuous learning and training.

Yet beyond compliance, experience shows that human factors—leadership, communication, teamwork, and fatigue management—are what truly make the difference in critical situations.

This article offers an in-depth look at preparedness and training as fundamental pillars in the making of a professional mariner. It combines regulatory references, real-world case studies, and practical tools to serve as both reflection and guidance for captains, officers, and safety managers committed to strengthening the safety culture within their crews.

Response Time and Muscle Memory in Maritime Emergencies

At sea, seconds make the difference between control and disaster. The speed with which a crew member reacts to an emergency does not depend solely on theoretical knowledge but on the ability to turn that knowledge into automatic action. This is where muscle memory comes into play. Repeating procedures through training and drills allows critical actions to be carried out without hesitation, reducing reaction time and avoiding mistakes.

Various studies in behavioral sciences and operational safety show that under extreme stress, the human brain tends to freeze or slow down if tasks have not been sufficiently internalized. On the other hand, when procedures have been realistically practiced, for example through fire drills, abandon ship exercises or man overboard recovery, the muscles respond automatically, freeing the mind to focus on strategic decision-making.

Regulatory Framework

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) officially recognizes this need to turn practice into conditioned reflex:

The STCW Convention of 1978 as amended (Section A-VI/1) requires all seafarers to complete basic training in firefighting, first aid, survival at sea and personal safety, with mandatory practical exercises

SOLAS Chapter III establishes that each crew member must participate in regular fire and abandon ship drills, with reaction times measured and evaluated by officers.

The ISM Code requires companies to maintain a documented program of drills and exercises, with results tracking to ensure continuous improvement

These regulations reflect a simple principle, training is not only about instruction but about engraving critical procedures into the sailor’s muscle memory. The more realistic the drill, the greater the agility in response during a real situation.

Operational Benefits

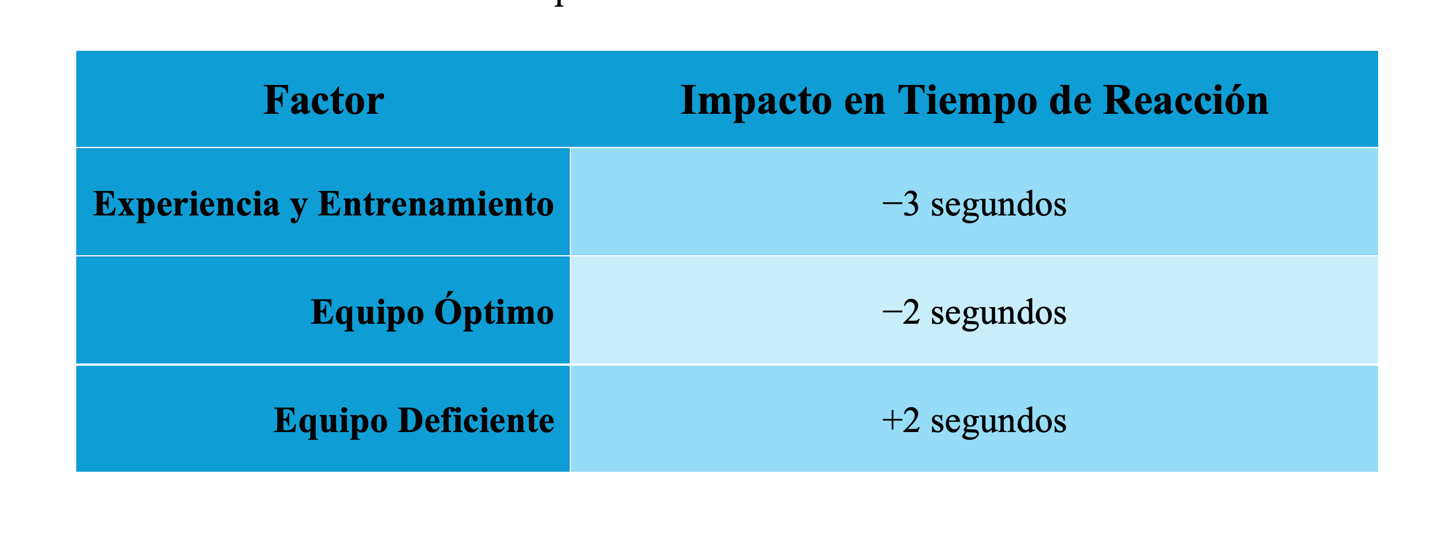

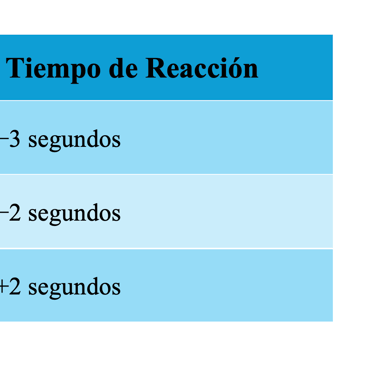

Reduction of the critical response interval: Regular practice decreases hesitation in the initial moments of an emergency.

Improved team coordination: By automating individual movements (e.g. using a fire extinguisher, closing hatches, donning a lifejacket), mental capacity is freed for communication and group cooperation.

Confidence and resilience: A regularly trained crew acts with greater confidence, reducing panic and increasing efficiency in crisis management

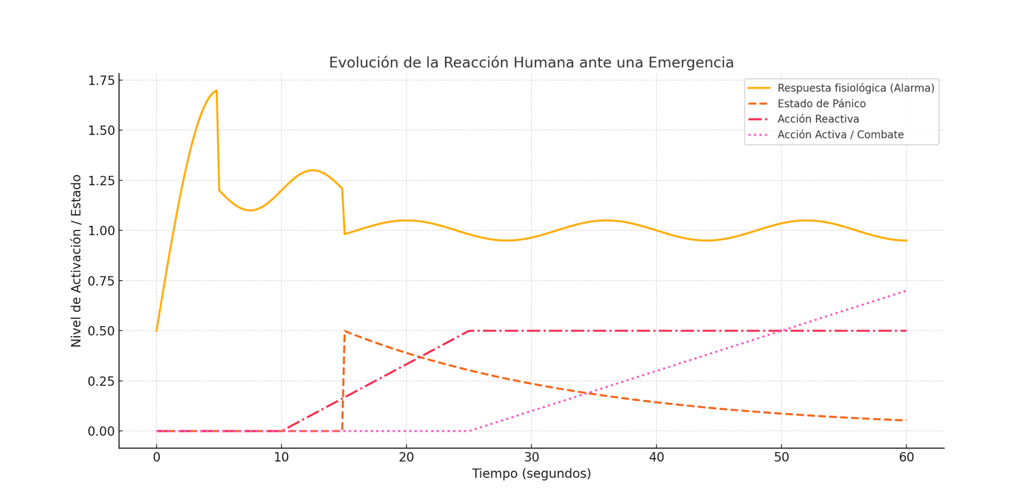

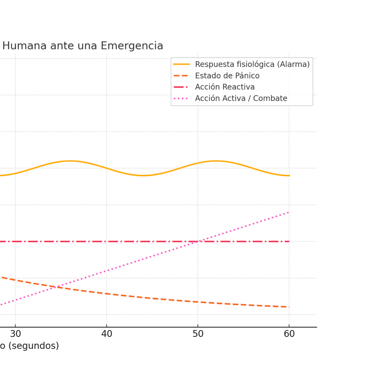

Operational psychology studies in the maritime field show that the response to a crisis follows a well-defined pattern. Understanding these phases allows both mind and body to be trained to act effectively under pressure.

Physiological response – Alarm phase (0 to 15 seconds): As soon as danger is detected, the body enters survival mode. Adrenaline is released, the heart rate increases and the senses sharpen. This activation prepares the sailor to react, although it can also cause an initial shock that blocks action or generates impulsive movements without a clear objective

Critical decision – Reactive action (15 to 25 seconds): Once the initial impact has passed, the body moves into a phase of automatic movements. This is the moment to trigger an alarm, grab a fire extinguisher or cut a line. Effectiveness in this phase depends directly on repetition in training, which turns these maneuvers into automatic reflexes

Active action – Combat phase (after 25 seconds): With the mind and body stabilized, tactical decisions begin based on knowledge and experience. This may mean cutting the fuel supply before attacking the flames or performing an evasive maneuver at high speed.

In a real scenario, a sailor could extinguish a fire alone only if it is tackled in its initial phase. At that moment, skill is decisive for prioritizing actions, alerting the crew and, if possible, containing the threat before it spreads.

Regulatory and Technical Framework of Maritime Preparedness

Crew preparedness and training are not optional but an international regulatory obligation. The International Maritime Organization (IMO), through its conventions and codes, establishes the standards that ensure every seafarer can respond effectively in emergency situations.

STCW Convention 1978 (amended in Manila 2010)

Establishes minimum standards of competence, training, and certification for seafarers.

Every crew member must be trained in:

Personal survival at sea (Section A-VI/1-1)

Fire prevention and firefighting (A-VI/1-2)

Basic first aid (A-VI/1-3)

Personal safety and social responsibilities (A-VI/1-4)

Includes advanced courses (e.g. crisis and crowd management on passenger ships, A-V/2)

This regulatory framework directly links practice with the reduction of response times, reinforcing what was outlined in the previous section.

SOLAS Convention 1974 (as amended)

Chapter III – Life-saving appliances and arrangements:

Requires abandon ship and firefighting drills at least once a month (Regulation 19)

Establishes that the maximum time to embark the crew into survival craft during a drill must be less than 10 minutes

Chapter IX – Safety management (ISM Code): introduces the mandatory link between shipping companies and their crews in the implementation of emergency plans and training.

ISM Code (International Safety Management Code)

Created after the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster (1987)

Requires each shipping company to implement a Safety Management System (SMS), which includes:

Written emergency procedures

Documented drills with recorded reaction times

Continuous review to correct deficiencies

Reinforces the idea that safety does not depend solely on the individual but on the entire organization.

Other relevant frameworks

MARPOL: although focused on pollution prevention, it requires training for responding to environmental incidents

IMO Model Courses: model courses that define how standardized training should be delivered in maritime academies

ILO (Maritime Labour Convention, 1996; MLC 2006): regulates minimum rest hours for seafarers to prevent fatigue, a factor directly linked to response time

The combined regulatory system STCW–SOLAS–ISM–MLC forms a comprehensive training and preparedness framework aimed at ensuring every crew is capable of responding quickly, in a coordinated and effective manner during emergencies, regardless of the vessel, flag, or company.

The Human Factor in Maritime Safety

Experience shows that even with modern ships and certified crews, accidents still happen. The main cause is often the human factor, recognized by the IMO as both the most vulnerable and the most decisive element of maritime safety.

Leadership and Decision-Making

In critical situations, the clarity of leadership from the captain and officers makes the difference. The IMO, through the STCW (Sections A-II/1 and A-III/1), states that training must include Bridge Resource Management (BRM) and Engine Room Resource Management (ERM), where decision-making under pressure, task distribution, and effective authority are practiced.

In the Costa Concordia disaster (2012), the lack of clear leadership and the delay in giving the abandon ship order caused loss of life that could have been avoided.

Communication and Teamwork

Crew Resource Management (CRM), adapted from aviation, is essential in the merchant marine. It trains crews in

Clear and direct communication, even in multicultural contexts

Standard use of Maritime English (SMCP – Standard Marine Communication Phrases, IMO)

Coordination of signals and roles to avoid duplication or gaps in action

The sinking of the Estonia (1994) revealed disorganization during evacuation many passengers did not understand the instructions and the crew was not sufficiently trained in crowd control.

Fatigue the Silent Enemy

Numerous maritime accident reports point to fatigue as a determining factor. STCW and the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC, 2006) establish

A maximum of 14 working hours within a 24-hour period

A minimum of 10 hours of rest in a 24-hour period

A minimum of 77 hours of rest in a 7-day period

Fatigue affects alertness, short-term memory, and motor reflexes, increasing reaction times. This is why fatigue management is just as important as conducting drills.

In the Exxon Valdez case (1989), one of the contributing factors identified was crew fatigue, which played a role in the human error that caused one of the worst oil spills in history.

Safety Culture

Beyond regulation, the onboard safety culture is what ensures the effectiveness of training. A crew that understands that drills are not a formality but a vital exercise will react automatically and in coordination. The ISM Code requires shipping companies to promote this culture from ashore, involving fleet officers, shipowners, and captains in a unified safety system.

Practical Tools to Strengthen Preparedness

International regulations (STCW, SOLAS, ISM) define what must be trained, but real success in an emergency depends on how that training is carried out. For this, crews need simple, clear, and repetitive tools that allow them to internalize procedures until they become reflexes.

Emergency Checklists

Checklists are essential allies in avoiding omissions under pressure. They may include

Fire on board steps for locating, isolating, communicating, and initial extinguishing

Abandon ship assigned roles, survival equipment check, route to muster stations

Man overboard emergency maneuver, signaling, throwing lifebuoys, assigning lookout

On ro-ro ferries, after the Estonia (1994), crowd control checklists became mandatory under STCW A-V/2.

Action Flowcharts

Visual diagrams help simplify critical decisions, especially in the engine room or on the bridge

Rudder failure diagram switch to hand steering → activate emergency hydraulics → notify the bridge → adjust speed

Engine room fire alarm shut off fuel → close ventilation → sound general alarm → initiate initial response team

Continuous Training Plans

The ISM Code requires documented programs. An effective training plan includes

Monthly drill calendar (fire, abandon ship, man overboard, oil pollution)

Role rotation so that every crew member practices different functions to avoid rigidity

Reaction time evaluation to measure how long it takes the crew to complete each procedure

Immediate feedback a short debrief to highlight strengths and areas for improvement

Digital Resources and Simulators

The IMO recommends the use of navigation and engine room simulators to train for high-risk situations without exposing the actual vessel

Collision, grounding, and propulsion failure simulations

Crisis and crowd management training on passenger ships

Integration of VR/AR (virtual and augmented reality) in training centers

Effective preparedness combines

International regulations (STCW–SOLAS–ISM) as a mandatory framework

Practical tools (checklists, flowcharts, training plans, and simulators) that turn theory into action

In this way, seafarers not only comply with administrative requirements but develop operational habits and muscle memory that allow them to act quickly, precisely, and confidently during real emergencies.

Maritime safety is built on three inseparable pillars

Realistic training

Regulatory compliance

Effective management of the human factor

Experience shows that the difference between a controlled emergency and a tragedy lies in the crew’s ability to respond in critical seconds. That ability does not come from improvisation but from repeated practice, muscle memory, and a safety culture shared by everyone on board.

The major accidents of recent history remind us of the cost of weaknesses in these pillars

Herald of Free Enterprise (1987) led to the ISM Code by highlighting the need for safety management systems in shipping companies

Estonia (1994) led to strengthening SOLAS and training in crowd control after the dramatic disorganization during evacuation

Costa Concordia (2012) reopened the debate on leadership and discipline during emergencies, showing that even on modern ships, crew preparedness is the decisive factor

These disasters, beyond the human tragedy, left lessons now embedded in international conventions. However, each new generation of seafarers must remember that rules only come to life when they are transformed into action and that constant training is what turns the crew into a true line of defense against the unexpected.

Points for Reflection

¿Are we training enough for our responses to become automatic reflexes in a real emergency?

¿Are we conducting drills as a mere administrative requirement or as a vital exercise that can save lives?

¿As captains and officers, are we promoting a genuine safety culture where preparedness is valued as much as navigation itself?